Jupyter Notebooks vs Excel VBE.

After spending several months with Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) within the MS Excel environment, I found myself at a crossroads. The efficiency VBA provided in automating tasks was undeniable; however, I was missing a more modern and flexible programming environment. Also, the inability to code outside MS Office programs made VBA less attractive. I decided to research solutions that would still allow me to easily interact with spreadsheet like data structures and have the capabilities of MS Excel while being more convenient for a person without a CS background.

Python programming language has a very strong position in the engineering environment as an approachable and pleasant to learn. Particularly enticing element is the extensive number of libraries containing engineering calculations, which additionally simplifies the creating automation for mechanical calculations. Compared to VBA, which doesn’t have nearly as active a community as Python and access to the aforementioned libraries, made me decide to jump the VBA ship and dive into the Python.

Next, I came across Jupyter. It’s an open source project that revolves around the development of the Jupyter Notebooks. Web-based application that allows users to create and share documents combining live code, equations, plots, and regular text. Paired with Python, it is presented to be the perfect starting point to step away from Excel based VBA and still work on engineering automation.

Jupyter Notebooks offer a significant advantage over Excel programming environment, with being language agnostic, allowing users to choose technology of their preference. Unlike Excel, which relies on VBA (Visual Basic for Applications), which despite being pleasant to start with, is not the most popular choice for developers nowadays. It also supports data visualizations, images, gifs and LaTeX equations. Although I am primarily focused on using Python as a programming language, it is worth noting that notebooks support over 40 programming languages to code with. It allows user to choose suitable technology depending on the purpose of the project and seamless integration with modern services, APIs, etc. Additionally, Jupyter’s support for version control mechanisms surpasses the capabilities of VBA, which by default is not supported and requires elaborate setup and third party extensions to be fully functional.

Jupyter Notebooks

To begin, the installation of Jupyter Notebook on your local machine is a prerequisite, following the installation of Python language. It can be installed separately or as part of the bundled Anaconda Distribution. While an alternative method involves using pip (Python package manager), opting for Anaconda is recommended as it provides numerous libraries that will be beneficial for applications dealing with datasets.

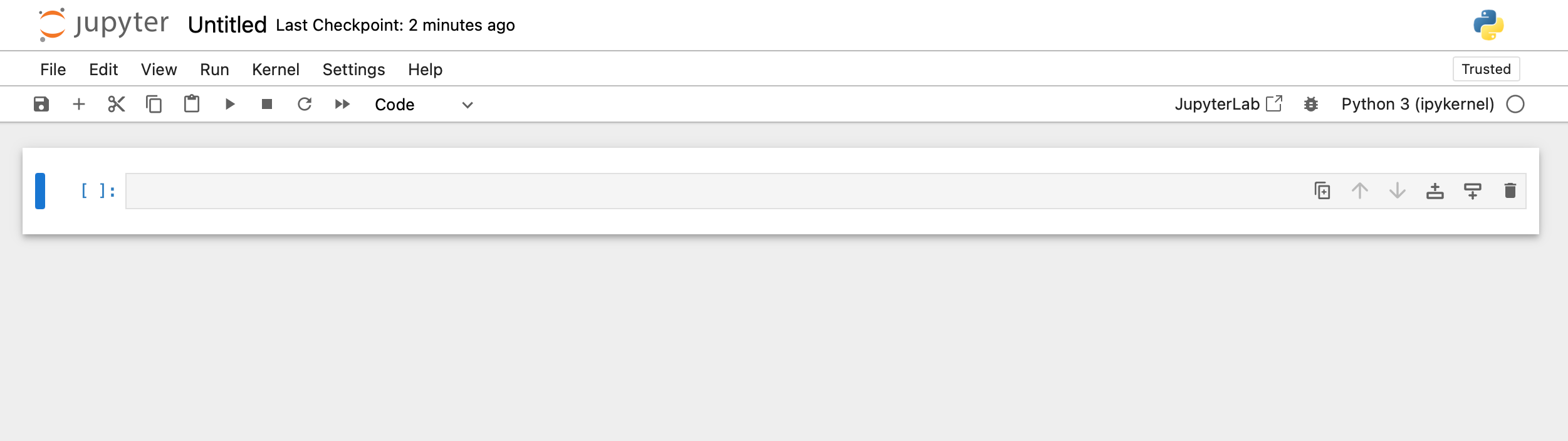

To launch the notebooks, you can run the Anaconda Navigator and choose the notebook in the Dashboard, or simply type jupyter notebook in terminal (the exact command may vary depending on your operating system). This command opens a web browser with Jupyter dashboard displaying the contents of the current directory. Navigate to the desired location and create a new notebook. You have the option to choose Python, Markdown or regular text file, but the most interesting for now is a Notebook option. This choice combines both markdown and Python code together. This will open up a new tab in your browser with an empty notebook prompting you to choose a kernel, proceed with Python3. Your browser should look as follows:

Notebook Interface

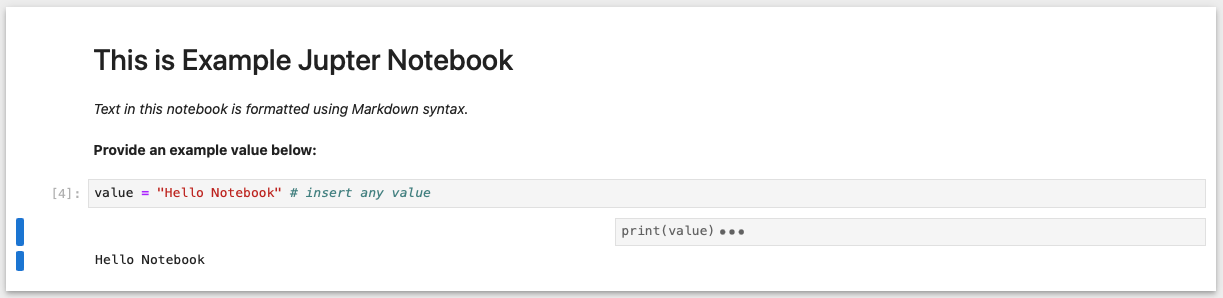

When launching the Notebook, the first thing you may have noticed is the input field in the middle of the screen. This is a cell. Cells may store various contents, but primarily there are two types of cells. One that contains Python code, and the other that contains Markdown code. Python cells are where you write and execute your Python code. You can create a new code cell by clicking the “+” button in the toolbar or by pressing B (for “below”) while in command mode (blue cell border). To execute a code cell, press Shift + Enter. The result will be displayed below the cell.

Markdown cells are used for adding text explanations, documentation, or LaTeX equations using Markdown syntax. You can create a new Markdown cell by clicking the “+” button in the toolbar and selecting “Markdown” from the dropdown menu. You can render the Markdown text the same way as executing code in Python cell, using Shift + Enter. Markdown is a simple markup language that uses plain text-formatting syntax to create rich-text documents. It allows users to simply format

and structure text using simple symbols. It is common among many text editors, and you can use it to a style text of README file in your GitHub repository or stackOverflow question. You can choose how you want the Jupyter to interpret highlighted cell by selecting its type on the toolbar dropdown.

The combination of Python and Markdown cells enables users to create well-formatted templates, exceptionally beneficial even for those that are not proficient in programming. A simple example is demonstrated below:

Additionally, a function I personally found incredibly convenient, particularly in the early stages of coding, is the flexibility in executing cells. In Jupyter Notebooks, you have the option to execute all cells in the notebook collectively, proceeding sequentially from top to bottom, or execute each cell individually. The feature proved to be valuable when dealing with an elaborate chain of calculations. Instead of relying on debugging and breakpoints, which may be not entirely clear for beginners, I organized my project such that each cell handled a fundamental piece of code. Executing cells one by one allowed me to quickly check intermediate values of variables, ensuring that the code is working as intended. Once confident that everything works correctly, I merged the code into a single cell resulting in well-structured and concise calculation.

Version Control and Code storage

Initially, the storage and saving location of notebooks might seem unclear. While running notebooks from the terminal, the Jupyter dashboard presents the directory from which the command was executed. By default, newly created notebooks or other files are saved in the same location. To ensure project synchronization across multiple devices, you consider saving your notebooks in a directory within a GitHub repository, or in your DropBox directory. I would recommend using GitHub, since it provides an extensive version control, allowing you to track every change. Moreover, it allows others to collaborate with you on the project.

Storing individual notebooks on GitHub involves manually running git commands from the terminal. JupyterLab is supplied with its git extension improving and simplifying the process. JupyterLab will have a separate article coming in the following weeks, but in essence, it is an entire development environment. It offers more options in terms of managing notebooks, widgets and custom interactive components. Furthermore, JupyterLab can be deployed on your custom domain and server, were you can build entire data science structure and also use it as a cloud-based storage for your projects. It does require more work, and I do not consider it feasible to investigate for individual/educational purposes.

Summary

In my experience, Jupyter Notebooks stand out as a fantastic project, serving as an excellent entry point for both beginners stepping into programming for engineering or data science and individuals, like myself, who have found VBA to be less exciting over time. The initial steps in this project are straightforward, specifically given the extensive community support around notebooks and Python. Additionally, it serves as an excellent platform for acquainting oneself with Python, laying a solid foundation for a transition to writing standalone applications in a full-blown IDE in the future.

Useful resources

Jupyter project: jupyter.org.

Quick start quide: jupyter docs.

Notebooks tutorial: Dataquest Beginner’s tutorial.